In the early hours of Sunday morning, the world awoke to historic news. The decades-old Assad regime had been toppled and, more than ever, a new beginning for Syria was in sight. But a democratic and free Syria is not guaranteed by the ongoing war of annexion waged by Turkey and Turkey-backed jihadists. Like a sword of Damocles, the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime threatens peace and stability in the region.

Different actors – different perspectives

After the fall of the Assad regime and the first celebrations, the question of Syria’s future looms large. While Western media portray the HTS and its leader al-Cholani as a moderate Islamist force that has learned from the past and broken ties with jihadist groups such as al-Qaeda and ISIS, displaced people from Aleppo and Sheba tell a different story. HTS remains a coalition of former Al-Qaeda organisations, ISIS splinter groups, local warlords and mercenaries. The threat and danger of the SNA is similar to that of the HTS, but the HTS is currently working more in the interests of NATO and the SNA more in the interests of the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime. Al-Cholani’s proposal to create a council for Syria should be taken with a pinch of salt. While the HTS ruled Idlib with an iron fist and cracked down on any opposition, DAANES in Rojava and Northern Syria developed governance based on grassroots democracy, women’s liberation and social ecology. But the biggest threat to Syria’s future comes from the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime. Turkey’s anti-Kurdish and neo-Ottoman war of annexation could plunge Syria into an even bigger abyss than the one it has experienced in the last decade. Therefore, it is crucial for the different actors in Syria and for the global forces to understand the motivation of the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime.

Historical Background of Neo-Ottomanism

We will focus on two driving motivations behind Turkey’s involvement: 1. Its imperialist neo-Ottoman dreams and 2. Its racist Kurdish paranoia. When the Ottoman parliament met for the last time on 28 January 1920, it decided on the future borders of a reformed Ottoman Empire, summarised under the term Misak-i Milli or National Oath. In response, colonialist British and French armies attacked the region and the Kurdish, Circassian and Arab War of Independence began. The decisions of the Misak-i Milli were later revoked in the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1923. All agreements with the Kurds, Circassians and Arabs were also revoked and under the rule of Mustafa Kemal Turkey was designed as a homogeneous nation-state. However, this Misak-i Milli and especially the borders of a greater Turkey later became a focal point of the Turkish-ultranationalist imagination. But this Turkish-ultranationalist reference to the Ottoman Empire is not just a romanticisation of the former “eternal state”. In the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic of Turkey, there are historical discontinuities as well as continuities. “Some historians believe that the borders established by the national treaty include Cyprus, Aleppo, Mosul, Erbil, Kirkuk, Batumi, Thessaloniki, Kardzhali, Varna and the [Greek] Aegean islands,” Erdogan said. These words are no coincidence; they define the ideological basis of the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime’s foreign policy.

The Erdogan-Bahçeli regime and neo-Ottomanism

Today, with the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime, the expansion of the Turkish state’s borders according to the Misak-i Milli has become an official state policy, which is labelled as neo-Ottomanism. This neo-Ottomanism even plays a role in the restructuring of the Turkish state and its foreign policy. First and foremost, the Turkish state has been centralised around the palace with the forceful introduction of the presidential system. Erdogan even built himself the ‘Cumhurbaşkanlığı Sarayı’, the presidential palace with a thousand rooms, in order to symbolically celebrate himself as a neo-sultan. The various ministries, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, don’t have any autonomy anymore, but directly implement the directives of the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime. This is very important for the smooth functioning of the war bureaucracy. Secondly and most interestingly, there are some similarities between the war strategy of the Ottoman Empire and the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime. The Ottomans used special units such as the Janissaries (“new soldiers”), the Akincis (“raiders”) and the Bashi-bazouks (“madmen”). In particular, the highly organised Akincis and the more unpredictable Bashi-bazouks – mercenaries, outlaws and ex-soldiers – were used as vanguards for reconnaissance and irregular warfare. These special forces were used to scout, raid, terrorise and destabilise the enemy before the main occupation army followed. Today, under the conditions of a multipolar and confrontational world order, we see the reappearance of such irregular special forces. Accordingly, the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime is also trying to integrate such forces as ISIS, SNA and HTS into its neo-Ottoman war strategy. For example, the SNA – which was built, financed and directed by the Turkish state – consists of various mercenary groups such as the jihadist and Turkish-nationalist Sultan Murad Division and Sultan Suleiman Shah Brigade, the Salafi-jihadist Ahrar al-Sharqiya and Jaysh al-Islam, and the jihadist and Syrian-nationalist Al-Mu’tasim Division and Hamza Brigades. These mercenary forces are known for their ruthless terrorism against the local population and enemy forces and are currently a major destabilising factor in Syria.

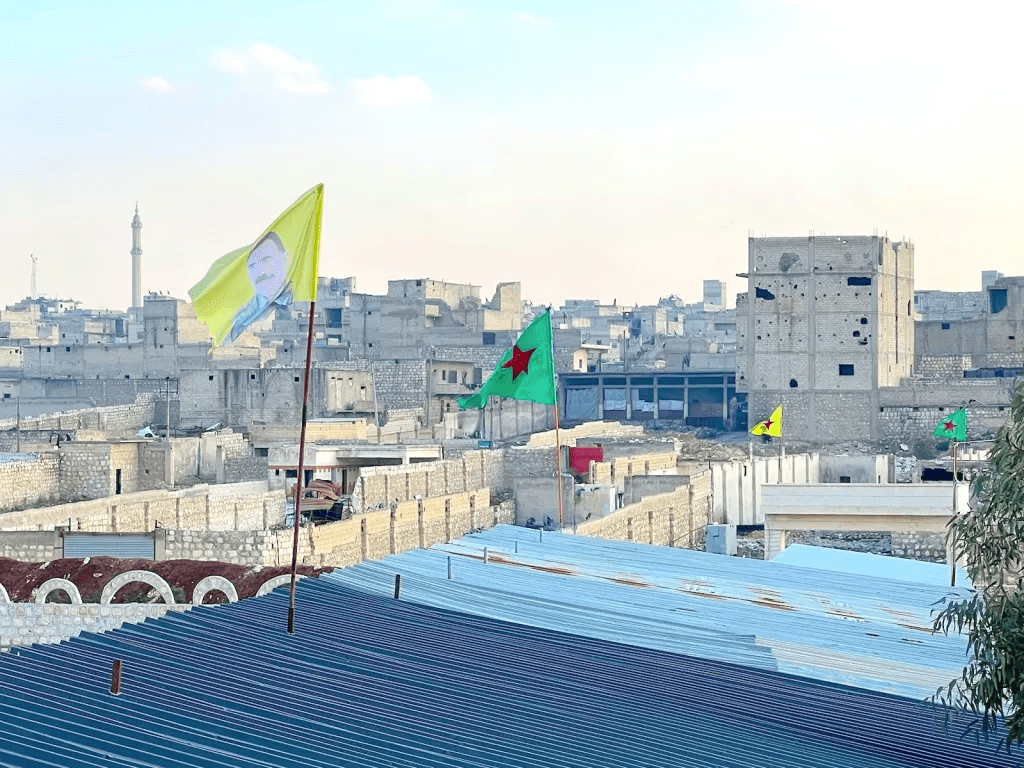

Autonomous Administration’s civilian security forces. 8 December 2024.

Racist Kurdish paranoia

But this analysis is not enough to understand Turkey’s foreign policy today. Having built its nation-state on a homogeneous and exclusionary foundation, every indigenous people of Anatolia and Mesopotamia, such as Kurds, Armenians, Assyrians, Pontos Greeks, Alevis, Ezidis, Jews, Arabs, Circassians and Laz – to name but a few – became a threat to the new artificial and socially constructed Turkish identity. During the transition from empire to republic, most of these indigenous peoples were subjected to a policy of massacre, most notably during the genocides of the Armenians, Assyrians and Pontic Greeks. The Kurds remained in the region inside and outside Turkey’s borders. Not only were and are the Kurds a significant force – they are, in fact, the largest stateless people in the world – but their very existence as indigenous and native to these lands was and is a threat to Turkish nationalist identity. That is why Turkish nationalism has developed a paranoia about Kurdistan, and the Kurds have become a projection screen for the fears and dreams of Turkish nationalism. The slightest look from the eyes of a Kurd or the sound of the Kurdish language strikes fear into the soul of the Turkish nationalist. Whenever and wherever Kurdish society asserts its cultural, economic and political existence, the fragile construct of Turkish nationalism collapses. Turkish nationalism, in turn, equates its existence with the assimilation, enslavement and extermination of the Kurds. Every pain inflicted on the Kurdish natives is experienced as relief and satisfaction by the Turkish colonialists. This is the ultimate motivation of the Turkish state policy since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey. The Erdogan-Bahçeli regime has integrated this anti-Kurdish racism into its neo-Ottoman dreams, so that the genocidal regime established by Mustafa Kemal one hundred years ago is now being extended from Northern Kurdistan to Southern and Western Kurdistan. In this way, Erdogan sees himself not only as a sultan, but also as a “second Atatürk”.

Turkey’s annexation strategy since 2015

In short, we can say that Erdogan’s policy is a combination of a) the ambition for a bigger Turkish state in the region and b) the Turkification of Kurdistan since the foundation of the Turkish Republic. That is why Erdogan is eagerly trying to “take back” multi-ethnic cities like Aleppo, Manbij, Mosul and Kirkuk, i.e. to occupy, annex and turkify them. That is why Erdogan, like no other power, is sowing the seeds of discord between peoples and societies in Syria. We could say that Erdogan has taken the phrase “divide and conquer” and modernised it to “destabilise and annex”. However, due to the resistance of Kurdish society, the fragmented nature of Kurdistan and the geopolitical constraints of powers like NATO and Russia, Erdogan has not been able to achieve these goals directly. The Turkish state is thus engaged in a low-intensity war, i.e. a gradual and varied annexation of Kurdistan. After witnessing the defeat of ISIS in Kobanê and feeling threatened by the unity of the Kurdish people during the Kobanê Serhildans, Erdogan ended the peace negotiations in the summer of 2015. Under the conditions of peace and growing social freedom, his nationalist-Islamist ideology lost more and more influence. So Erdogan changed his strategy. For Rojava this meant a strategy of destabilisation by means of jihadist groups, low-intensity war and economic embargo, with consequent occupations when the geopolitical opportunity arises, as it did from August 2016 to March 2017 when Turkey occupied Cerablus, Bab and Ezaz, from January 2018 to March 2018 when Turkey occupied Efrîn, and in October 2019 when Turkey occupied Girê Spî and Serêkaniyê – and today. In all these operations, Turkey used the Syrian National Army (formerly known as the Free Syrian Army) as its direct proxy in Syria and other more loosely affiliated jihadist groups, such as today’s HTS.

Turkey was directly involved in the Second Artsakh War (also known as Nagorno-Karabakh), which began in 2020 and ended in autumn 2023 with the total annexation of this indigenous Armenian territory by the Azerbaijani army. Whether in terms of political and material support, or directly in military terms through the participation of Turkish officers and numerous fighters from the “Grey Wolves”, an ultra-nationalist Turkish organisation, the Turkish regime played a full part in this war of annexation. Erdogan and Aliev often like to point out that Turkey and Azerbaijan are two states but one nation, referring to the pan-Turkic ideology. Just a few days ago, the ultra-nationalist and Erdogan’s accomplice Devlet Bahçeli declared that “Aleppo is Turkish and Muslim to the bone” in order to justify the current expulsion and ethnic cleansing of Kurds, Yezidis, Christians, Armenians, Assyrians, Greco-Syriacs and non-Sunni Arabs and Turkmens. At the time of writing, 10 December 2024, it has been announced that Manbij, which was previously part of the Autonomous Administration (DAANES) territory, is now under Turkish military occupation. Fighting is already continuing in the direction of Kobanê.

The Turkish annexation of Efrîn

But the occupation doesn’t end there. We can see this most clearly in Efrîn, which has been occupied by the Turkey-backed SNA since 2018. In Efrîn, they have – unsurprisingly – established a reign of terror that includes systematic looting, abductions, torture, violence against women, forced displacement and resettlement programmes, and the destruction of Kurdish and Yazidi heritage. In only 6 years more than 10 000 persons have been kidnapped. Sunni Arab and Turkmen families of jihadist mercenaries are being settled there to create a ‘Turkish-Sunni belt’. Most interestingly, however, Efrîn is treated as an extension of Turkish territory, under the direct control of the Turkish military, intelligence and civil administration. In the education system, Kurdish has been replaced by Turkish as the primary language and schools follow the Turkish national curriculum, national history and national identity. The judicial system operates according to Turkish standards and the Turkish lira has been introduced as the currency. In short, the ethnic cleansing of the Kurdish population, which was reduced from 90% to around 10% of the total population, and the institutionalisation of the colonial administration laid the groundwork for the diplomatic negotiation of the annexation

Democratic confederalism for the future of Syria?

Now more than ever, the Democratic Confederalist project in Northern and Eastern Syria needs to be studied and discussed. The Western media’s attempt to push Al-Cholani’s proposal for a “council” in Syria ignores the realities in Syria. The autocratic rule of HTS in Idlib is not even remotely comparable to the achievements of the Rojava revolution. Not only is democratic confederalism based on grassroots democracy, women’s liberation and social ecology, but DAANES is the longest, most stable and only functioning government in Syria today. Under the rule of DAANES, we have seen ethnic and religious identities coexist peacefully. In this sense, the racist and nationalist politics of annexation are today the greatest threat to the future of Syria. Any local and global actor seriously interested in a solution should support or at least consult with DAANES. The biggest threat to Syria was and is the annexation policy of the Erdogan-Bahçeli regime. “Now the situation is changing. HTS is expressing itself differently. If HTS changes in practice and is no longer under the command of the Turkish state, we can talk and negotiate with each other,” said Salih Muslim of the PYD (Democratic Unity Party). So any negotiations on the future of Syria should include the DAANES, can be mediated by forces from outside Syria, but must be independent of them. As long as the Turkish occupation forces remain in Syria and the annexation war against the DAANES continues, the future of Syria remains uncertain.

Mahîr for Ronahî – Youth Center for Public Relations.